Park Güell.

In recent decades globalisation has transformed urban economies so radically that cities risk losing their identities, while at the same time globalisation forces them to become more visible. Many cities met this double challenge through placemaking: place marketing (putting themselves on the map) and place branding (creating new urban identities). The changes induced by place marketing and place branding, however, were largely superficial – a new logo, a new strapline, a new city marketing department.

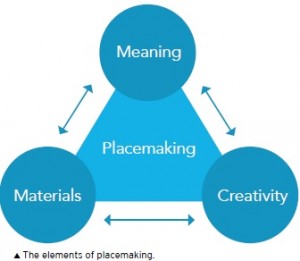

As Hildreth (2008) has argued, it is no longer enough for cities to change their image or brand – they need to improve their reality as well. In an increasingly networked and mobile society, any image or brand will quickly be checked against experience, and the real qualities of the place being promoted. So how do cities make themselves ‘the place to be’, especially when everywhere else also wants to be ‘the place to be’? If places need to improve their reality to meet the needs of an increasingly demanding marketplace, then they need to shift from a city marketing mindset to a placemaking mindset. In broad terms, placemaking is about shaping cities. But as Soja argued in his volume on ‘Thirdspace’, it is not just the physical reality of the city that matters, but also the way that reality is represented and lived or experienced. We can therefore conceive of placemaking as a social practice that involves three different elements: materials, meaning and creativity (see table). Good placemaking involves shaping the material reality of the city in order to give the lived spaces of the urban meaning for inhabitants and other users of the city.

As Hildreth (2008) has argued, it is no longer enough for cities to change their image or brand – they need to improve their reality as well. In an increasingly networked and mobile society, any image or brand will quickly be checked against experience, and the real qualities of the place being promoted. So how do cities make themselves ‘the place to be’, especially when everywhere else also wants to be ‘the place to be’? If places need to improve their reality to meet the needs of an increasingly demanding marketplace, then they need to shift from a city marketing mindset to a placemaking mindset. In broad terms, placemaking is about shaping cities. But as Soja argued in his volume on ‘Thirdspace’, it is not just the physical reality of the city that matters, but also the way that reality is represented and lived or experienced. We can therefore conceive of placemaking as a social practice that involves three different elements: materials, meaning and creativity (see table). Good placemaking involves shaping the material reality of the city in order to give the lived spaces of the urban meaning for inhabitants and other users of the city.

The Barcelona road to success

If we look at Barcelona for example, we can begin to see what makes things happen in the sphere of placemaking. Barcelona, driven by identity politics after the death of Franco, has arguably managed to balance all three aspects of the placemaking model in the development of the city.

The city was physically re-modelled through the regeneration effort linked to the 1992 Olympics. Urban regeneration created new cultural spaces, new visual icons and opened the city to the sea.. The representation of the city shifted from being the ‘Paris of the South’ to the ‘Capital of the Mediterranean’, supported by cultural icons including Miro, Dali and Picasso (Richards and Palmer, 2010). This also linked to the shifting image of the city from a port and business centre to a leisure and cultural destination. The lived experience of the city changed as more public space was punched into the dense fabric of the inner city and the city was linked more closely with the sea. The death of Franco gave the streets back to the people, leading to more public expression and animation as the ‘cultural isostasy’ (Richards, 2007) of the Catalan capital was restored with a boom in events, festivals and public facilities.

Greg Richards:

If after 1992 Barcelona was still suffering a post- Olympic hangover, at the end of the decade tourism had doubled and Gaudí was established as an iconic figure in design magazines and tourist guides.The combination of all these factors led to a renaissance of cultural production and consumption, creativity, architecture, economic activity and most notably tourism. If after 1992 Barcelona was still suffering a post-Olympic hangover, at the end of the decade tourism had doubled and Gaudí was established as an iconic figure in design magazines and tourist guides. In 1999 Barcelona even became the first city to win a RIBA Royal Gold Medal for its architecture.

Barcelona managed to maintain this momentum into the ‘noughties’, with a programme of event-years designed to follow up on the Olympic success story, including the phenomenally successful Gaudí Year in 2002. Events such as the very popular Sónar Festival also introduced the city to new audiences and created even more ‘atmosphere’ (Richards and Colom, forthcoming). Although events often took the headlines and boosted tourism, however, the micro-scale remodelling of the urban fabric was also crucial. Holes were punched into the dense fabric of the old city to bring light and create new spaces of interaction (or what Delgado and Richards 2003 termed ‘trusting spaces’). The new hard plazas also became visually iconic, as in the case of the Plaça dels Angels in front of the MACBA Contemporary Art Museum, which is still the backdrop for skateboarding video shoots. There was a recognition that these spaces could not instantly be turned into ‘places’, but that the patina of years of lived experience was necessary to make this happen.

Permeability, mutability, tangibility

In the Barcelona model of placemaking the success factors are threefold: permeability, mutability and tangibility. Permeability in making public space visible, accessible and readable; mutability in making spaces multifunctional, heterogeneous and flexible; tangibility in developing the reality behind the image of the city, which in turn impacts on the lived experience of all users of urban space. The Barcelona experience also underlines the recursive relationship between physical space, place and events. Large scale events require not just a time, but also a space in which to unfold. Barcelona is pock-marked with the traces of events, some of which like the Cuitadella Park or the Olympic Port have melded into and moulded the urban fabric. In all cases, however, the opening up of spaces by and for events creates a need for more events to provide animation, or the development of structures to provide more permanent forms of use.

It’s not all good news and triumphs however. The UNESCO-sponsored Universal Forum of Cultures in 2004 was an attempt at top-down placemaking which failed spectacularly. Originally conceived of as helping to complete Cerda’s original plan for the city, over three billion euros of private investment was generated for the many apartments, hotels and office blocks that filled the Diagonal Mar area. The cultural content of the event was less successful, partly because the linkage of the event with major corporations alienated many in the alternative sector, partly because of the removal of local communities to make way for the site and also because the marketing campaign was woefully inadequate. However, it was the lived experience that received least attention and which also caused most problems. The site itself was poorly designed, with vast open areas of concrete that were at best unwelcoming and hardly in keeping with the cultural intent of the event. Regular attempts at kickstarting social and cultural activity produced some hot-spots, but there was a total disconnect between the debates and conferences set up to discuss the state of global culture and the Forum site itself. Legacy planning was also totally absent, meaning the site remained an unused windy wasteland for years afterwards. So the Forum mobilised a lot of material assets, and also arguably involved a lot of creativity, but it totally failed to generate meaning for the city or its inhabitants.

The Barcelona case also underlines what McCann (2002) frames as the struggle between ‘culture’ and ‘economy’, or between exchange values and use values. Many now complain that the centre of Barcelona has become an open-air museum or theme park, with residents displaced by commercial development, gentrification and Airbnb. The privileging of exchange value threatens to destabilise the Barcelona placemaking model, even though the municipality appears to be fighting back with new controls on development and civic order.

Tourists as temporary citizens

One attempt to re-establish the primacy of use value for urban space has been a reframing of the meaning of space and its users. One of the interesting aspects of the latest urban plan for Barcelona for example, was the way in which tourists were re-positioned as ‘temporary citizens’. The change in role from consumers to citizens not only confers rights on the tourists as users of the city, but it also implies duties to be responsible tourists able to share the lived space of the city with others. It is perhaps too early to tell if this particular strategy has been a success, but monitoring of the attitudes of local residents towards tourism has shown a consistently high level of support for tourism in spite of the many episodic problems linked to tourism development (Richards, 2015). This seems to indicate that the residents of Barcelona are also aware that the relationship between physical space, the users of that space and the meanings attached to it can all be mutually influenced by placemaking processes.