Participatory Governance Map. Bron: http://themuseumofthefuture.com/

Earlier this year, many readers of this blog participated in a mapping of participatory governance practices in cultural heritage in Europe. Margherita Sani, Bernadette Lynch, Alessandra Gariboldi and myself used this input and our own research for a recent EENC report on the topic. In this post I present and reflect on some of our findings.

It used to be that if you needed to make sure you got a funder excited about your ideas, all you had to do was add post-its at the end of your exhibition and call it a participatory experience. True or not, participation is a buzzword and as such is often used to make things sound better than they really are. When we started mapping cases of participatory governance in cultural heritage, I feared I’d find many of these: Participation to tick a funder’s box.

Fortunately, we found a wide variety of cases where institutions and communities really tried and succeeded to govern cultural heritage participatory, at least to some extend. In Helsinki citizens work together on the planning and budgeting of new institutions, in the Baltics and Scotland ordinary people take responsibility for the maintenance of built heritage, while in the Netherlands and Germany people work together to document their shared heritage.

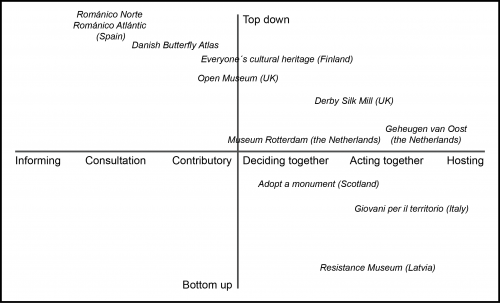

We defined participatory governance as the sharing of responsibility. Obviously, responsibility can be shared at many different levels, and in many different ways. To facilitate the discussion about this, in our report we developed a simple framework to compare cases of participatory governance. On the horizontal axis, we combined Wilcox Ladder of Participation with Nina Simon’s participation framework to distinguish different levels of participation. On the vertical axis, we show where a project has been initiated: bottom-up or top-down?

Cases towards the bottom and far right of the framework tend to make the best stories, including my current favourite about the Teatro Sociale of Gualtieri, where a group of young people independently of government decided to renovate an old theatre.

It’s a great joy studying the different cases and I greatly recommend you do so. Especially the extended case studies and special categories (which include the European Cultural Routes, UNESCO World Heritage Sites and others) provide pointers and starting points for institutions willing to experiment with participatory governance themselves. The shorter case studies present bright ideas and different approaches to participation, which can easily be copied.

The variety in the case studies is so wide, that it may seem that when it comes to participatory governance ‘anything goes’. This is not true. Even when projects are initiated bottom-up, they require a deliberate decision to be participatory, conscious design for participation and quite often courage and persistence on the part of the organiser. Participatory governance doesn’t happen automatically and it certainly does not happen by ticking a funder’s box. As the case of the Derby Silk Mill shows, you may actually have to convince the funder that something that is to some extend governed participatory is worthy of funding (it took them years).

For me, the mapping exercise poses two immediate questions (and please share your thoughts on them in the comments below):

- Can institutions gradually move up the Wilcox/Simon ladder of participation, or does such change require a disruptive transformation? I.e. can a contributory project such as the Danish Butterfly Atlas over time turn into a project where institution and community act together? The well-documented case of the Geheugen van Oost (detailed case study in the report) in the Netherlands seems to prove it can happen, but I don’t know of many other cases where they achieved such long-term sustainable change.

- What is the relation between the origin of a project and its sustainability? I.e. can a bottom-up project ultimately be as sustainable as cultural heritage institutions are traditionally designed to be? (Or likewise, can a strictly hierarchic top-down institution ultimately be sustainable in a time where community engagement is so important?). Various cases we found, such as the Teatro Sociale in Gualitieri, seem to prove there is not necessarily a relation between origin and sustainability. Bottom-up is just as long term as top-down.

The mapping exercise and report were only a first step in a wider project researching participatory governance in cultural heritage. I’ll be keeping an eye on the developments and will be sure to share any further developments with you on this blog.

Read the full report ‘Mapping of practices in the EU Member States on Participatory governance of cultural heritage’ on the website of the EENC.